Brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) aim to translate brain activity into commands or communication. Unlike invasive implants (e.g. Neuralink) that require surgery, non-invasive BCIs use sensors on the scalp to read brain signals. The two main non-invasive modalities are electroencephalography (EEG) and functional near‑infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). EEG uses scalp electrodes to detect electrical brain waves, while fNIRS shines harmless near‑infrared light into the cortex to measure blood oxygenation changes (similar to a miniaturised, portable fMRI). These methods trade off differently: EEG has very high temporal resolution (milliseconds) but low spatial detail, whereas fNIRS is slower (seconds) and limited to cortical areas but less prone to certain artifacts. Both approaches are affordable and portable, making them popular for research and potential consumer applications.

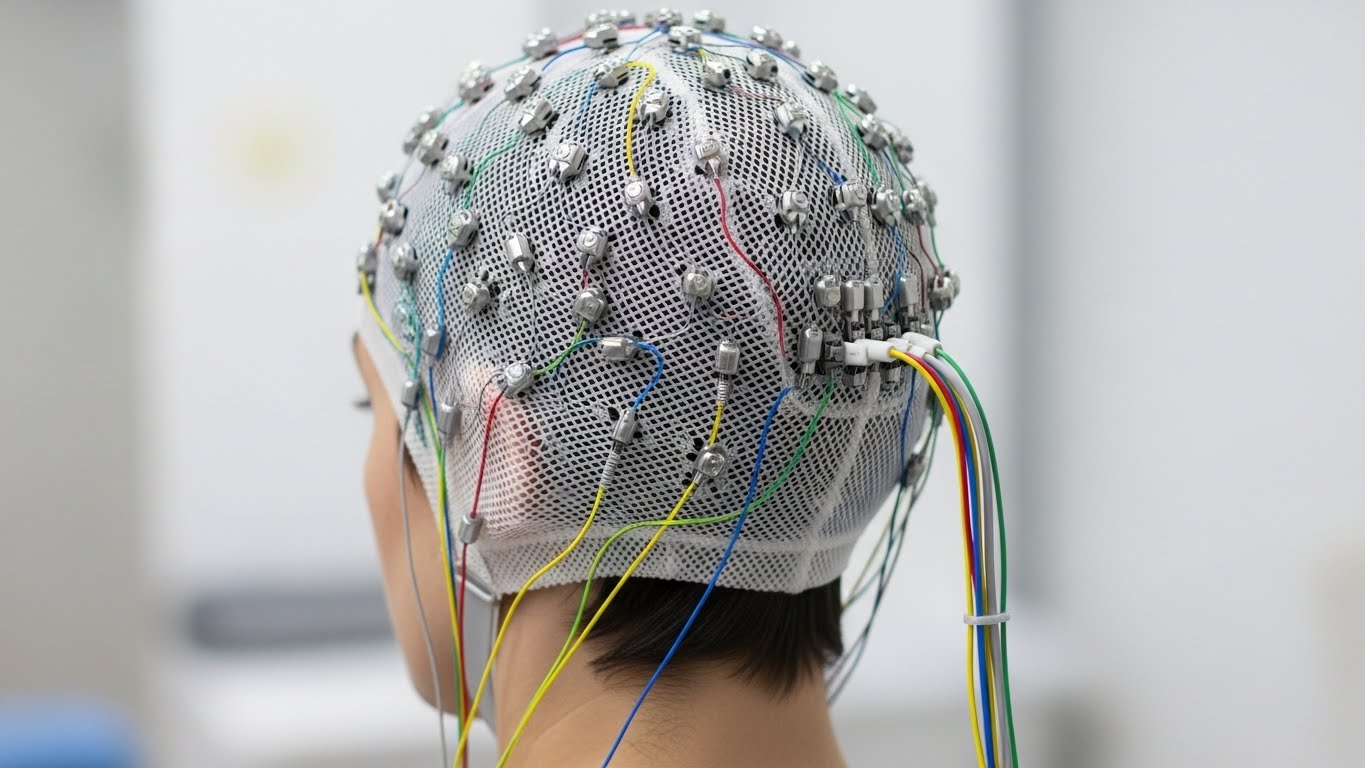

Electroencephalography (EEG) is the most common non-invasive BCI. EEG caps with many sensors record microvolt-scale brain waves. It excels at capturing rapid neural dynamics (e.g. attention or motor signals) and is used in many BCI applications (spellers, cursor control, neurofeedback). However, EEG signals are extremely weak – on the order of millionths of a volt – and are easily swamped by muscle movements, eye blinks or even blinking in bright light. In practice, subtle actions like frowning or breathing can distort the EEG. As a result, EEG BCIs often require careful filtering and user stillness. Despite this, modern wireless EEG headsets exist (some even for gaming) that can pick up robust signals once artefacts are handled.

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) uses light instead of electricity. A headband of light sources and detectors emits near‑infrared wavelengths (650–1000 nm) into the skull, and measures how much light is absorbed by oxygenated vs deoxygenated hemoglobin. Since active brain regions consume more oxygen, fNIRS infers neural activity from blood oxygen changes. This hemodynamic signal is slower (peaking ~5–10 seconds after a thought) but has advantages: it is relatively unaffected by eye or scalp muscle noise, and is safe and unobtrusive. fNIRS requires more complex optics (source-detector pairs) and usually samples a few centimeters into the cortex, but it can pick up deeper and different types of signals than EEG. In short, EEG captures fast electrical rhythms but is very noisy, whereas fNIRS captures slower metabolic changes and is more robust to movement. Researchers are increasingly combining EEG and fNIRS to get the best of both worlds. For example, a South Korean group showed that a hybrid EEG–fNIRS BCI could decode eight distinct commands (like mental arithmetic or eye movements) to control a drone, achieving ~86% accuracy with EEG and ~75% with fNIRS.

Decoding Speech from Brain Signals

A major goal is to decode speech or language from brain activity, which could restore communication for people who cannot speak (e.g. locked-in syndrome). In BCIs, “speech decoding” can mean different things: listening to speech (auditory perception), covertly imagining speaking (inner speech), or even attempting to speak while paralysed. Invasive implants (brain electrodes) have shown impressive speech decoding: for example, paralysed patients with implanted microelectrodes have achieved ~90 characters per minute and ~15 words/minute accuracy. But invasive BCIs require surgery and carry risks. Non-invasive EEG/fNIRS approaches promise safer alternatives, though they currently lag in performance.

Early non-invasive speech BCIs operate in constrained ways. For instance, EEG-based spellers allow a user to select letters one by one (e.g. by focusing on flashing rows of a grid). This P300 or steady-state visually evoked potential (SSVEP) approach has given some locked-in patients a way to “type” messages, albeit very slowly. More direct speech decoding (mapping EEG to actual words or phonemes) is an active research frontier. In lab settings, EEG signals have been used to classify a few spoken or imagined words or vowels. As one review notes, simple classification tasks (e.g. distinguishing between two vowels) can yield 70–80% accuracy with EEG, but more complex tasks (multiple words or free speech) drop to 20–50% accuracy. In practice, most non-invasive systems today handle very limited vocabularies or binary choices, not full sentences. For example, one study found EEG could distinguish five spoken vowels with only ~30–40% accuracy, whereas the same invasive BCI might do far better.

On the fNIRS side, researchers have shown it’s possible to decode aspects of heard speech. In a 2018 experiment, participants listened to recorded story segments while wearing an fNIRS cap, and a machine‑learning model could identify which of two segments they heard with about 75% accuracy. This was much better than chance (50%) and demonstrates that even slow blood‑flow signals contain speech information. However, fNIRS has not yet been used to decode imagined or covert speech in practice – it’s mainly been used for external tasks (like motor imagery or arithmetic) because the signal is sluggish.

More recently, AI and big-data techniques have pushed the boundaries. A Nature Machine Intelligence study (2023) used deep learning to align MEG/EEG data with large language models (specifically a Wav2Vec2 speech model). By training on hours of data, they could identify which of 1000 possible words a subject heard, achieving an average top-10 accuracy of ~41% (best subjects ~80%). This is essentially “listening” decoding and shows promise; however, it relies on having known reference speech and advanced models. It also focused on listening, not thinking speech. Still, it demonstrates that non-invasive sensors can carry rich linguistic information if coupled with AI.

Key breakthroughs to highlight include:

- Hybrid EEG–fNIRS BCIs: Combining modalities boosts performance. For example, Khan et al. (2017) merged fNIRS (mental tasks) and EEG (eye movements) to decode eight distinct control commands for a drone.

- Machine learning advances: New algorithms (like delay-differential methods) are matching deep neural networks for EEG speech decoding, offering faster, simpler processing.

- Semantic decoding datasets: Groups have begun gathering concurrent EEG/fNIRS data during concept tasks (e.g. imagining animals vs tools) to train “semantic BCIs” that recognise categories of thought.

- Auditory speech decoding: As noted, methods like those from Meta AI (open source) have decoded heard or imagined speech with unprecedented scale (over 700 subjects).

Overall, non-invasive “speech BCIs” are advancing, but still mostly in the research phase. They have demonstrated that some categories or words can be extracted from EEG/fNIRS under ideal conditions, but real-time, fluent thought-to-text remains elusive.

Practical Applications and Advances

Despite limitations, several practical applications are already envisioned or emerging:

- Assistive communication: The most immediate use case is helping people with paralysis or neurodegenerative disease to communicate. EEG spellers and BCI keyboards (for example, flashing matrix grids) allow letter-by-letter communication. In the future, decoded speech BCIs could let a patient “speak” full words or phrases by thought alone, once accuracy improves.

- Prosthetics and control: EEG/fNIRS BCIs can also drive external devices. As noted, multi-command BCIs have been used to fly drones or move wheelchairs. More complex imagined speech commands could one day launch smart home actions or write messages on social media without voice.

- Neurorehabilitation and games: Non-invasive BCIs (especially EEG neurofeedback) are used in stroke rehab and cognitive training. Gamified BCI applications already allow brain-controlled games or VR experiences. Speech decoding could enrich these – for instance, controlling a virtual assistant through thought.

- Research tools: Beyond end-use, speech BCIs provide insight into neuroscience. Decoding inner speech helps us understand how the brain produces language and could improve brain–computer communication generally. Datasets like the EEG+fNIRS semantic corpora offer resources for further innovation.

- Technology trends: On the tech side, commercial EEG headsets (dry electrodes, wireless) and research-grade fNIRS caps are becoming more user-friendly. AI developments (large language models, transformers) are being adapted to brain data. Some startups (e.g. OpenBCI) are promoting do-it-yourself EEG kits, and military/tech agencies are funding BCI research. These advances mean future BCIs may be faster (lower-latency decoding), smaller (portable headsets), and more capable (hybrid sensors, personalised AI models).

Major technical challenges remain, however:

- Signal quality: EEG’s low amplitude (μV) and susceptibility to noise, and fNIRS’s slow response and interference (ambient light sensitivity), limit performance. Short-duration thoughts may not produce clear patterns.

- Accuracy and vocabulary: Current non-invasive BCIs can usually distinguish only a few choices (e.g. yes/no, a set of letters or words). Scaling up to large vocabularies or open speech dramatically reduces accuracy.

- User training and variability: Each user’s brain is different; BCIs often need calibration. Fatigue, electrode placement, and attention levels can change results day-to-day.

- Speed: fNIRS is inherently slow (several-second delay), and even EEG-based spelling is much slower than natural speech or typing. Real-time continuous speech decoding is not yet feasible.

- Portability vs performance: Laboratory EEG/fNIRS setups may not work well in everyday settings. Motion and environmental factors can kill the signal, as noted above.

Ethical and Societal Considerations

Decoding thoughts raises profound ethical questions. Key concerns include:

- Privacy of thought: Brain data is deeply personal. EEG/fNIRS recordings could, in principle, reveal emotions, intentions or private associations. The notion of “neurorights” has emerged to address this. For example, the NeuroRights Foundation proposes rights to mental privacy and cognitive liberty – essentially protecting individuals from unauthorised reading or manipulation of brain data. In practice, this means requiring strong consent and data safeguards for any neurotechnology.

- Data security: BCI devices often connect to apps or cloud servers. There is a risk that brain data could be hacked or leaked. Unlike typical health data, neural data could be non-obvious – users may not even know what the device is capturing. Robust encryption and clear regulations are needed.

- Consent and autonomy: Many target users (e.g. severely disabled patients) have limited ability to revoke consent. Ensuring truly informed consent for research and clinical use is crucial. Users must understand what data is used and how.

- Neural bias and equity: Just as AI can be biased, BCI systems trained on certain populations may not work well for all (different brain anatomies, ages, cultures). There are also disparities in access – advanced BCIs could widen inequality if only available to wealthy or well-funded patients.

- Misuse and dual-use: There is concern that unscrupulous actors could misuse neural decoding for surveillance, marketing or coercion. For example, could employers demand brain scans to gauge honesty? While such scenarios are dystopian, some experts warn that popular media hype could underestimate the risk of gradual privacy erosion.

- Regulation: Some governments are already moving. Chile has amended its constitution to treat brain data like an organ and protect mental privacy. In 2024 California extended consumer privacy laws to include neural data, and Colorado and Montana passed similar neural-data protection bills (protecting data from wearables and games). The EU is studying “neurotech governance,” noting that existing laws (like data protection) may help, but suggesting specific oversight and public education. Overall, regulators are beginning to catch up: for now, one can say that neural data increasingly demands the same confidentiality as DNA or medical records.

In short, BCIs blur the line between mind and machine, so society must grapple with new questions. Advocates argue we should codify mental privacy rights before powerful neurotech becomes widespread. This includes not only privacy but also ensuring equitable access (to prevent “cognitive haves” and “have-nots”) and preventing misuse (criminal or commercial). Public discussion is growing, but policy is still nascent.

Global Research and Perspectives

BCI research is truly global.

- Europe hosts many BCI labs (e.g. UK, Germany, France) and has taken a lead on ethical policy. European Union groups have commissioned studies on neurotechnology regulation, and initiatives like the Human Brain Project (EU-funded) include BCI components. British and Italian teams, for instance, are investigating EEG/fNIRS for communication (including the hybrid semantic BCIs). The EU’s approach tends to emphasise safety and data rights, leveraging existing medical device laws and data-protection frameworks.

- North America (USA and Canada) has strong academic and industry involvement. US institutions (Stanford, Columbia, UC San Francisco, MIT, etc.) have published the majority of recent EEG/MEG speech-decoding breakthroughs. Tech companies (Meta AI, Kernel, Facebook’s Reality Labs) are funding ambitious brain-recording projects. Canadian and Mexican groups are also active in hybrid BCIs. In policy, California led with SB1223 (2024) treating neural data as a protected category, and U.S. neurosurgeons have called for federal rules on neurorights. However, most North American work still focuses on the invasive or EEG research frontiers rather than consumer fNIRS.

- Asia is rapidly expanding in neurotechnology. China has major R&D programs (both civilian and military) in BCI, though much of the recent high-profile work (e.g. Shanghai’s EEG-hybrid speech projects) is invasive. Chinese companies also sell EEG and fNIRS devices. South Korea and Japan have long traditions in neuroimaging: Korean labs (like Pusan National University) develop EEG-fNIRS hybrids; Japanese scientists pioneered fNIRS (the technique itself was invented in Japan) and continue to explore its use for communication and cognitive measurement. India has emerging BCI labs focusing on low-cost EEG systems. Japan and South Korea are also drafting guidelines for brain tech and privacy. While detailed policies vary, the Asia-Pacific region recognises the strategic value of BCIs (for AI leadership, elder care, etc.) and is investing heavily, with parallel concern for user consent and ethics.

In summary, from Silicon Valley to Shanghai, from Brussels to Brasília, governments and researchers recognise both the promise and the pitfalls of speech-decoding BCIs. Recent reviews and news highlight global attention: for example, the UNESCO Courier (2023) lauds Chile’s efforts to protect neurorights, while advocacy groups point to new laws in U.S. states. At the same time, international conferences (like those of the IEEE Brain Initiative) showcase cutting-edge labs from all continents. The result is a dynamic landscape where scientific advances are quickly followed by policy debates.

Conclusion

Non-invasive speech BCIs sit at the frontier of neuroscience, AI and ethics. On one hand, they offer hope: a mute patient dreaming of speaking again might someday have their thoughts translated into words without surgery. On the other hand, the technology is still nascent and faces real hurdles. Accuracy and speed remain far below natural communication, and the “mind-reading” potential raises deep privacy issues.

The coming years will likely see steady progress: better EEG/fNIRS hardware, more sophisticated ML models (perhaps trained on cloud datasets of brain signals), and refined hybrid systems. But this progress must go hand-in-hand with clear rules and public dialogue. Protecting mental privacy and consent is as important as boosting signal accuracy. Only with both technological maturity and ethical safeguards can speech-decoding BCIs fulfill their promise – empowering those who’ve lost their voice, while respecting the privacy and rights of everyone’s most personal data: their own thoughts.

Key takeaways: non-invasive BCIs like EEG and fNIRS are safe and portable but face signal challenges; recent studies have shown proof-of-principle speech decoding in the lab; applications range from patient communication aids to hands-free control; and as devices improve, issues of privacy and regulation (neurorights) are becoming urgent. The field is vibrant globally, blending neuroscience, engineering and ethics, with breakthroughs on the scientific horizon that will shape society as much as they aid individuals.

Sources

Frontiers | Hybrid EEG–fNIRS-Based Eight-Command Decoding for BCI: Application to Quadcopter Control

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neurorobotics/articles/10.3389/fnbot.2017.00006/full

Frontiers | fNIRS-based brain-computer interfaces: a review

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00003/full

European Parliament | The Protection of mental privacy in the aea of neuroscience

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2024/757807/EPRS_STU(2024)757807_EN.pdf

Decoding speech perception from non-invasive brain recordings | Nature Machine Intelligence

https://www.nature.com/articles/s42256-023-00714-5?error=cookies_not_supported&code=4d6321d9-b029-43cc-8e46-dd5d06a1ddbb

Frontiers | Decoding imagined speech with delay differential analysis

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/human-neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2024.1398065/full

A State-of-the-Art Review of EEG-Based Imagined Speech Decoding – PMC

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9086783/

Frontiers | Speech Recognition via fNIRS Based Brain Signals

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/neuroscience/articles/10.3389/fnins.2018.00695/full

Simultaneous EEG and fNIRS recordings for semantic decoding of imagined animals and tools | Scientific Data

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-04967-0?error=cookies_not_supported&code=24b25984-60bc-46c7-b0cf-b0a7654855b1

Chile: Pioneering the protection of neurorights | The UNESCO Courier

https://courier.unesco.org/en/articles/chile-pioneering-protection-neurorights